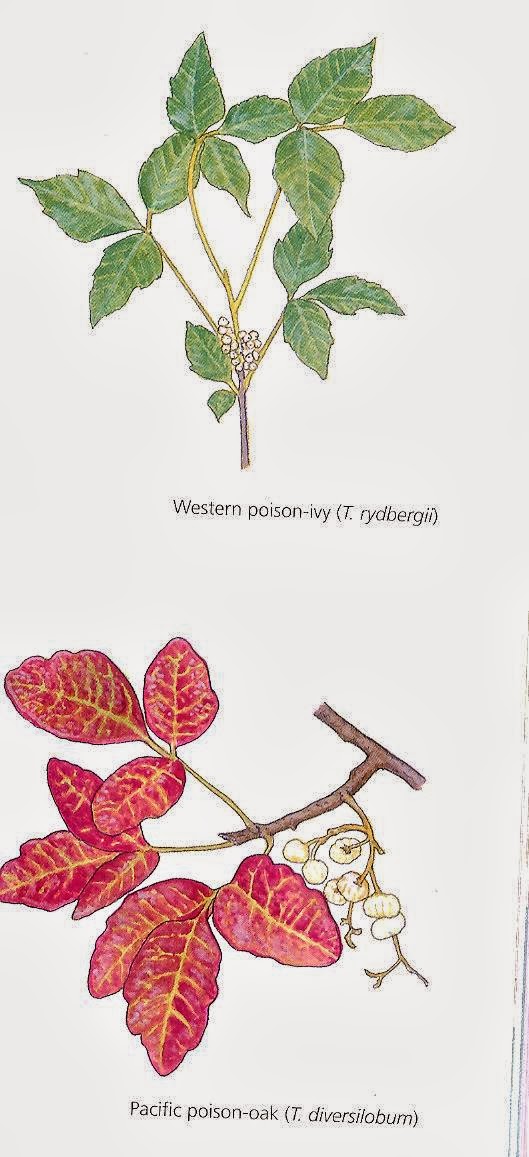

Poison oak is a deciduous shrub,

which like POISON IVY IS in the SUMAC FAMILY, native to North America.

Its

leaves contain a compound that causes a rash on human skin.

Poison Oak can Specifically Refer to:

Toxicodendron pubescens, which grows in Eastern

North America

Toxicodendron diversilobum, which grows in Western

Coast of North America

Poison oak (Toxicodendron diversilobum) and its EASTERN

COUNTERPART poison ivy (T. radicans) are two of the North American plants most

painful to humans.

Note: These

species were formerly placed in the genus Rhus. Poison oak and a related,

look-alike shrub, Rhus trilobata belong to the SUMAC family (Anacardiaceae).

Poison oak is widespread throughout the mountains

and valleys of the western USA. It thrives in shady canyons and riparian habitats.

It commonly grows as a climbing vine with aerial (adventitious) roots that

adhere to the trunks of oaks and sycamores.

Rocky Mountain poison oak (Toxicodendron rydbergii)

occurs in canyons throughout western Canada. Because the two species of

western poison oak look like a vine as they develop, some

authors list poison oak as a subspecies of eastern poison ivy.

Poison oak often

grows like a climbing vine.

The cautionary rhyme "leaves of three, let it

be" applies to poison oak, as well as to poison ivy (Toxicodendron

radicans). Toxicodendron diversilobum, commonly named Pacific poison oak or

western poison oak (syn. Rhus diversiloba), is in the Anacardiaceae family (the

sumac family).

The woody vine or shrub is widely distributed in

western North America, inhabiting conifer and mixed broadleaf forests,

woodlands, grasslands, and chaparral biomes. It is known for causing itching

and allergic rashes in many humans, after contact by touch or smoke inhalation.

The Pacific poison-oak Toxicodendron species is

found in California, Nevada, Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia. The closely

related Eastern poison oak (Toxicodendron pubescens) is native to the

Southeastern United States. Pacific poison-oak and Western poison-ivy

(Toxicodendron rydbergii) hybridize in the Columbia River Gorge area.

Toxicodendron diversilobum is common in various

habitats. It thrives in shady and dappled light through full and direct

sunlight conditions, at elevations below 5,000 feet. The vine form can climb

up large shrub and tree trunks into their canopies. Sometimes it kills the

support plant by smothering or breaking it.

The plant often occurs in chaparral and woodlands,

coastal sage scrub, grasslands, and oak woodlands; and Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga

menzesii), Hemlock—Sitka spruce, Coast redwood (Sequoia sempervirens), Yellow

Pine (Pinus ponderosa), and mixed evergreen forests.

Description

Toxicodendron diversilobum, Pacific or western

poison oak, is extremely variable in growth habit and leaf appearance. It grows

as a dense one and a half to thirteen foot, tall shrub in open sunlight; also as a tree like vine

ten to thirty feet high and may be more than more than one hundred feet long with a three to eight inch trunk. It reproduces

by spreading rhizomes and by seeds.

Pacific Poison-oak foliage.

The plant is deciduous, so that after

cold weather sets in, the stems are leafless and bear only the occasional

cluster of berries. Without leaves, poison oak stems may sometimes be

identified by occasional black marks where its milky sap may have oozed and

dried.

The leaves are divided into three (rarely five,seven or nine) leaflets, one and one a half to four inches long, with scalloped, toothed, or lobed edges. They

generally resemble the lobed leaves of a true oak, though the Pacific poison

oak leaves will tend to be glossier. Leaves are typically bronze when first

unfolding in February to March, bright green in the Spring, yellow-green to

reddish in the Summer, and bright red or pink from late July to October.

White flowers form in the spring, from March to

June. If they are fertilized, they develop into greenish-white or tan berries.

Botanist John Howell observed the toxicity of

Toxicodendron diversilobum obscures its merits:

"In spring, the ivory flowers bloom on the

sunny hill or in sheltered glade, in summer its fine green leaves contrast

refreshingly with dried and tawny grassland, in autumn its colours flame more

brilliantly than in any other native, but one great fault, its poisonous juice,

nullifies its every other virtue and renders this beautiful shrub the most

disparaged of all within our region”

Pacific poison oak leaves and twigs have a surface

oil, urushiol, which causes an allergic reaction. It causes contact dermatitis-

an immune-mediated skin inflammation- IN 4/5 OF HUMANS However, most, if not

all, will become sensitized over time with repeated or more concentrated

exposure to urushiol.

Pacific Poison-Oak grows on drier

rocky slopes at lower elevations on south-eastern Vancouver Island and nearby

Gulf Island.

Reactions:

Urushiol-induced contact dermatitis from poison

oak.

Pacific poison oak skin contact first causes

itching; then evolves into dermatitis with inflammation, colourless bumps,

severe itching, and blistering. In the dormant deciduous seasons the plant

can be difficult to recognize, however leafless branches and twigs contact also

causes allergic reactions.

Contrary to what has been written by

other authors and posted on other web-sites Urushiol volatilizes when burned;

SO IT IS, INDEED, CARRIED THROUGH THE AIR to unsuspecting victims.

And,

human exposure to Toxicodendron diversilobum smoke is extremely hazardous, from

wildfires, controlled burns, or disposal fires. The smoke can poison people who

thought they were immune. The resin can persist on pets and

clothing for months and is also ejected in fine droplets into the air when the

plants are pulled.

Branches used to toast food over campfires can

cause reactions internally and externally, although, or so it is claimed, the

Karok peoples traditionally used them as a cooking tool.

Ecology: Black-tailed deer, Mule deer, ground

squirrels, Western grey squirrels, and other indigenous fauna feed on the

leaves of the plant. It is rich in phosphorus, calcium, and sulphur. Bird

species use the berries for food, and utilize the plant structure for shelter. Native

animals, horses, livestock, canine pets, DO NOT demonstrate reactions to

urushiol.

Due to human allergic reactions, Pacific poison oak

plants are usually eradicated in gardens and public landscaped areas. It can be

a weed in agricultural fields, orchards, and vineyards. It is usually removed

by pruning, herbicides, digging out, or a combination of these.

Uses:

Native North Americans used the plant's stems and

shoots to make baskets, the sap to cure ringworm, and as a poultice of fresh

leaves applied to rattlesnake bites. The juice or soot was used as a black dye

for sedge basket elements, tattoos, and skin darkening.

An infusion of dried roots, or buds, eaten in the

spring, were taken by some native peoples for an immunity from the plant

poisons.

Chumash peoples used Pacific poison-oak sap to

remove warts, corns, and calluses; to cauterize sores; and to stop bleeding.

They also drank a decoction made from Pacific poison-oak roots to treat

dysentery.

© Al (Alex-Alexander) D Girvan> All rights reserved.

© Al (Alex-Alexander) D Girvan> All rights reserved.

No comments:

Post a Comment